Metaphysics & Ancient Greece: Why did Plato believe in ‘Forms’?

Plato is considered one of the greatest thinkers of the ancient world. His Theory of Forms, also called Theory of Ideas, proposes one of the most influential contributions made towards Western thought and towards the understanding of the nature of reality, knowledge and morality. His theory introduces a solution to various philosophical problems that he observed in what he considered to be the transient, chaotic and changeable nature of the physical world and that which he saw as imperfect and therefore an unreliable source for the understanding of true knowledge. Plato used the idea of Forms to serve him as a higher metaphysical reality that would account for all the above-mentioned issues regarding the imperfections within the physical world and could address concepts such as universals and particulars, establish ethical and ontological standards and provide a solid foundation for true knowledge. To understand why Plato believed in these Forms requires exploring the metaphysical, epistemological and ethical motivations underpinning his theory as well as the intellectual challenges he faced from other philosophers and movements during his time.

For Plato the idea of Forms derives first and foremost due to his personal distrust of the sensory experience of the physical world; his belief was that the sense of touch, taste and sight can be considered deceptive at times and therefore an unreliable and unpredictable source of knowledge. He believed the physical world to be filled with objects and concepts which are constantly changing, imperfect and transient and he argued that knowledge must be certain, permanent and unchanging for it to be constituted as what he considered to be true knowledge, or episteme. This point is reiterated in the dialogue Theaetetus, where Plato explores the nature of knowledge and contrasts it with mere belief or opinion. He suggests that all things in the material world are constantly changing and because of this then no stable knowledge can be derived from them. “Plato insists that sense perception can never yield knowledge because the objects of sense are in a constant state of flux, and knowledge must be about what is stable and unchanging.” [1]

To address all these concerns and to understand fundamental questions about reality and knowledge Plato proposed the existence of a higher metaphysical reality: abstract, eternal entities which as mentioned above he called “Forms”. For Plato these Forms exist beyond the physical world and to him constituted a solution to true reality as for him they represent perfect and unchanging archetypes of all things, from abstract concepts such as the idea of beauty to the reality of physical objects such as a table or a chair. In Republic, he expresses the distinction between the visible world, which is perceived through the senses and the intelligible world which is accessed through reason when he stated that "the many beautiful things are seen but are not known by reason, while the forms are known by reason but are not seen." [2] This statement reflects why he required Forms as his belief is based on the idea that sensory perception captures only the appearances of things or concepts, not the immutable truths that underlie the reality of them.

In her book An Introduction to Plato’s Republic, Julia Annas elaborated that for Plato the Forms serve as "ideals that particular things strive to resemble but can never fully achieve." [3] For example, a furniture object such as a table or a chair may strive to embody the Form of Chairness, but it will have a number of limitations due to its material composition, physical attributes and the subjectivity of human craftsmanship of the very person that made that particular chair. Plato therefore believed that only the unchanging idea of Forms would provide the criteria by which one can judge imperfection in the physical world, as these Forms then offer a measure of perfection beyond the sensory experience and can show the ideal version of what a chair should be. Therefore one of the reasons for this theory of Forms, was for Plato to resolve his belief in what he felt was a tension between the flawed physical world and the human capacity to conceive perfect ideals, affirming his belief in a higher metaphysical reality. The metaphysical distinction between the world of Becoming, which Plato believed encompasses the sensory realm, and the world of Being, which for him represents the realm of Forms, is fundamenta to himl. This distinction lays the foundation for why he needed to believe in the existence of these ideal, perfect Forms, because he viewed them as the true reality, in contrast to the ever-changing and imperfect material world of senses and opinions. He articulates this division in the example of the Allegory of the Cave, found in Republic [4], which expresses his belief in the theory of Forms by illustrating the journey from ignorance to enlightenment. In the allegory, prisoners are confined in a dark cave, forced to perceive only shadows cast on a wall in front of them. These shadows symbolise the deceptive nature of sensory experiences, which Plato regarded as mere illusions and opinions of reality. He explained, “The truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.” [5] This condition represents, for Plato, humanity’s epistemic limitation when relying solely on the senses, as the physical world provides an incomplete and distorted reflection of the true reality, which Plato believed lies only in the idea of Forms.

The allegory continues it’s narrative with the escape of one prisoner which symbolised the philosopher’s intellectual journey towards enlightenment. Upon leaving the cave, the prisoner initially struggles to adjust to the bright light of the sun, which represents the Form of the Good. Plato describes this progression from the darkness to enlightenment: “At first he would most easily see the shadows, and after that the reflections of men and other things in the water, and later the things themselves.” [6] This ascent from the dark to the light and then adjusting to the brightness illustrates the philosopher’s gradual understanding of the Forms, culminating in the recognition of the Good, the ultimate principle that illuminates and sustains all other Forms. Gregory Vlastos emphasises that this cave’s imagery seen by the prisoners conveys Plato’s belief in a dual reality which is further reiterating why Plato required Forms; because the physical world, to him, is considered a flawed imitation of a higher, intelligible realm. Vlastos argues, “The cave is not just an image of human ignorance but a powerful metaphor for Plato’s metaphysical hierarchy.” [7] Plato describes the Form of the Good as the utmost pinnacle of the metaphysical hierarchy, similar to how the sun that enables clearer vision and the creation of life in the material world. It is by understanding the Form of the Good that Plato believed one gained knowledge of all other Forms, as his belief is that this was the ultimate principle of intelligibility and existence and one of the reasons for his belief in Forms.

Plato’s belief in Forms is also connected to his attempt to resolve the philosophical problem of universals, which concerns how multiple particular objects can share common qualities or participate in universal concepts. In the dialogue Euthyphro, Socrates’ questioning revolves around the nature of piety, seeking a universal definition that captures the essence of all pious acts. For Plato, the failure of Euthyphro to provide such a definition underscores the necessity and need for his belief in a universal Form of Piety that grounds and unifies all instances of pious behaviour. Without the theory of Forms, Plato contended, it would be impossible to explain how one can recognise commonalities across diverse experiences or how it would be possible to have meaningful discourse about abstract concepts without the use of these Forms. Plato articulates this idea further in Parmenides where he elaborates that “each Form exists as one over the many,” [8] meaning that a single, immutable universal underlies the multitude of its manifestations. Miller underscores this as a cornerstone of reasoning for Plato’s metaphysical framework: “Plato’s realm of Forms is his solution to the metaphysical and epistemological challenges posed by the problem of universals” [9] Therefore for Plato, the theory of Forms is not merely a speculative construct but a necessary foundation for explaining how one can conceive universal and abstract concepts as well as how to recognise their many manifestations in a diverse and ever-changing world which further solidified his need and believe in these Forms.

Plato’s metaphysical commitment and conviction to his belief in the Forms is also evident in his treatment of mathematics and geometry. In dialogues such as the Meno and Timaeus, Plato highlights the precision and universality of mathematical truths, which are independent of the physical world. Furthermore, Plato’s belief in the Forms can also be understood as a response to the relativism of the Sophists and the skepticism of earlier philosophers such as Heraclitus and Protagoras which is why he believed in the Forms. The Sophists argued that truth and morality are relative, varying according to individual or cultural perspectives. Plato opposed this view, arguing that without objective standards, meaningful discourse and ethical behaviour would be impossible. For Plato his belief withheld that the Forms provided unchanging and universal entities and an objective foundation that counters the relativism of the Sophists and supports the possibility of universal truth and morality. While Heraclitus claimed that “you cannot step into the same river twice,” [10] emphasising the ever-changing nature of the world, Plato’s view was that the theory of Forms offered a stabilising counterpoint, asserting that these Forms offer a permanence to the underlying and apparent chaos of the sensory world.

In conclusion, Plato’s belief in the theory of Forms arose from his desire to provide a metaphysical foundation for knowledge, ethics, and the intelligibility of the world. It accounted for the existence of a separate, immutable realm of perfect entities that Plato believed served to resolve the problems posed by the impermanence and deceptiveness of the sensory world. He believed that Forms served as the ultimate standards of truth, beauty, and justice, grounding both philosophical inquiry and practical life.

Bibliography

Annas, Julia, An Introduction to Plato’s Republic (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981)

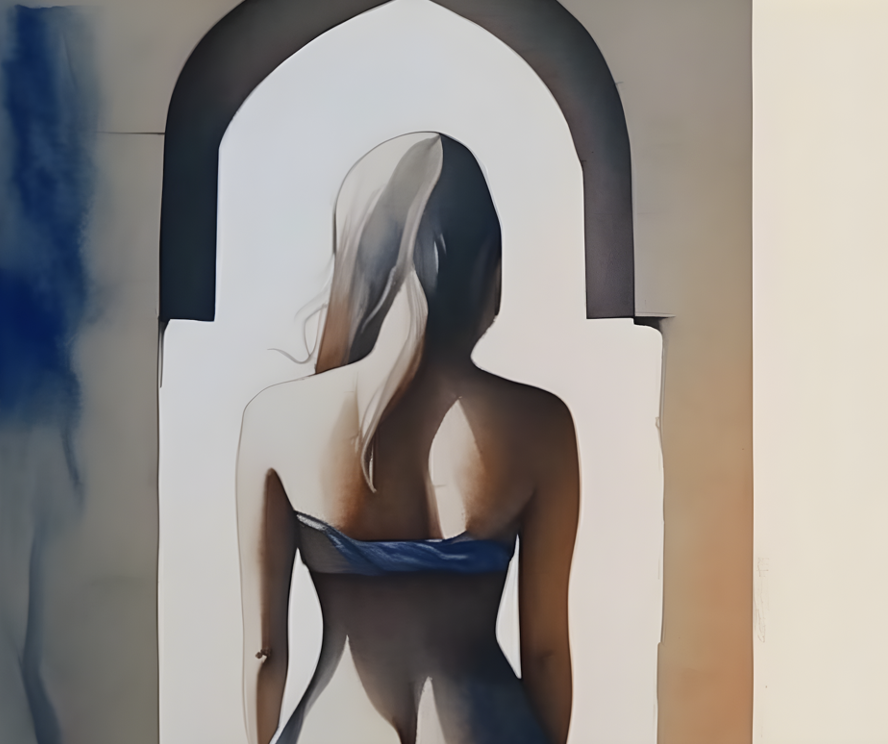

Drakopoulou, Elle, Cave Allegory, watercolour, 2024.

Kirk, G. S., J. E. Raven, and M. Schofield, The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983)

Miller, Fred D. Plato’s Parmenides: Text, Translation, and Introductory Essay. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999)

Plato, Parmenides. Trans. by R.E. Allen (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997)

Plato, Republic, trans. by Robin Waterfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008

Vlastos, Gregory, Platonic Studies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981)

[1] Gail Fine, Plato on Knowledge and Forms: Selected Essays (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 14.

[2] Plato, Republic, trans. by Robin Waterfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), Book 507b

[3] Julia Annas An Introduction to Plato’s Republic (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981) p. 252.

[4] Plato, Republic, trans. by Robin Waterfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), Book 514a – 520a

[5] Plato, Republic, trans. by Robin Waterfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), Book 515c

[6] Plato, Republic, trans. by Robin Waterfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), Book 516a

[7] Gregory Vlastos, Platonic Studies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981) p. 75.

[8] Plato, Parmenides, trans by R.E. Allen (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997) 130b

[9] Fred Miller, Plato’s Parmenides: Text, Translation, and Introductory Essay (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999) p. 12

[10] Heraclitus, Fragment 12, The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, trans. by G.S. Kirk, J.E. Raven, and M. Schofield (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), p. 186.